Understanding Rust Lifetimes

No, seriously, this time for real

Coming to Rust from C++ and learning about lifetimes is very similar to coming to C++ from Java and learning about pointers. At first, it looks like an unnecessary concept, something a compiler should have taken care of. Later, as you realize that it gifts you with more power — in case of Rust it is more safety and better optimizations — you feel encouraged to master it but fail because it is not exactly intuitive and the formal rules are hard to find. Arguably, C++ pointers are easier to get immersed into than Rust lifetimes because C++ pointers are everywhere in the code, while Rust lifetimes are usually hidden behind tons of syntactic sugar. And so you end up being exposed to the lifetimes when syntactic sugar does not apply which is usually some complex cases. It is hard to internalize the concept when the only things you are exposed to are the complex cases.

Intro

The first thing one needs to realize about lifetimes is that they are all about references, and nothing else. For example, when we see a struct with a lifetime type-parameter it refers to the lifetimes of the references owned by this struct and nothing else. There is no such thing as a lifetime of a struct or a closure, there are only lifetimes of the references inside the struct or the closure. Therefore our discussion of the lifetimes will inevitably be about Rust references.

The motivation behind the lifetimes

To understand the lifetimes we first need to understand the motivation behind them, which requires understanding the motivation behind the borrowing rules first. The borrowing rules state:

At no point in the code, there are references to overlapping pieces of memory, a.k.a aliasing, such that at least one of them is used to mutate the content of the memory.

Simultaneous mutation and aliasing are undesirable because it is unsafe and it prevents the compiler from doing various optimizations.

Example

Suppose we wanted to write a function that shifts the given coordinates along the x-axis twice in the given direction.

struct Coords {

pub x: i64,

pub y: i64,

}

fn shift_x_twice(coords: &mut Coords, delta: &i64) {

coords.x += *delta;

coords.x += *delta;

}

fn main() {

let mut a = Coords{x: 10, y: 10};

let delta_a = 10;

shift_x_twice(&mut a, &delta_a); // All good.

let mut b = Coords{x: 10, y: 10};

let delta_b = &b.x;

// shift_x_twice(&mut b, delta_b); // Compilation failure.

}

The last statement would have shifted the coordinate three times instead of two which could cause all kinds of bugs in the production system. The core problem is that delta_b and &mut b point to an overlapping memory, which is prevented in Rust through lifetimes and borrowing rules. Specifically, Rust compiler notices that delta_b requires holding an immutable reference to b until the end of main(), but in that scope, we also attempt creating a mutable reference to b, which is prohibited.

To be able to perform the borrowing rules check compiler needs to know the lifetimes of all references. In many cases compiler is able to derive the lifetimes on its own, but sometimes it is unable to and that’s where the developer needs to step in and annotate them manually. Additionally, it gives the developer a design tool, e.g. one can require that all structs that implement a certain trait have all their references live for the given duration, at least.

Compare Rust references to C++ references. In C++ one can also have const and non-const references, similarly to Rust’s x and &mut x. However, there are no lifetimes in C++. This helps C++ compiler with optimizations a bit, but it does not give complete safety guarantees. And so the above example would compile if it was written in C++.

Desugaring

Before we dive deep into understanding lifetimes, we need to clarify what a lifetime is, because various Rust documentation uses word lifetime to refer to both scopes and type-parameters. Here we say lifetime to denote a scope and lifetime-parameter to denote a parameter that compiler would substitute with a real lifetime just like when it infers types of generics.

Example

To make explanation transparent we will desugar some Rust code. Consider the following snippet:

fn announce(value: &impl Display) {

println!("Behold! {}!", value);

}

fn main() {

let num = 42;

let num_ref = #

announce(num_ref);

}

Here the desugared version:

fn announce<'a, T>(value: &'a T) where T: Display {

println!("Behold! {}!", value);

}

fn main() {

'x: {

let num = 42;

'y: {

let num_ref = &'y num;

'z: {

announce(num_ref);

}

}

}

}

The following desugared code was explicitly annotated with lifetime-parameter 'a and lifetimes/scopes 'x, 'y, and 'x.

We have also used impl Display to compare lifetime-parameters with general type-parameters. Notice how sugar was hiding both a lifetime-parameter 'a and a general type-parameter T. Note, the scopes are not a part of the Rust language syntax, we use them for annotation purposes only, and so this code will not compile. Also, in this and other examples, we ignore non-lexical lifetimes that were added in Rust 2018 to simplify the explanation.

Subtyping

Technically, lifetime is not a type, because we cannot construct an instance of it, unlike regular types like u64 or Vec<T>. However, when we parametrize functions or structs lifetime-parameters are used just like they were type-parameters, see the above announce example. Also, Variance rules that we will see later operate with lifetimes like they were types, so we will go along with calling them types in this post.

It is useful comparing lifetimes to regular types, and lifetime-parameters to regular type-parameters :

- When compiler infers a type for a regular type-parameter it would complain if there are multiple types that can satisfy the given type-parameter. In the case of lifetimes, multiple lifetimes can satisfy the given lifetime-parameter and the compiler would take the minimal one.

- Simple Rust types do not have subtyping, more specifically, a struct cannot be a subtype of another struct, unless they have lifetime-parameters. However, lifetimes allow subtyping, and so if lifetime

'longercompletely encloses the lifetime'shorterthen'longeris a subtype of'shorter. Lifetime subtyping also enables limited subtyping on types that are parameterized with lifetimes. As we will see later this implies that&'longer intis a subtype of&'shorter int. The'staticlifetime is a subtype of all lifetimes because it is the longest.'staticis kinda opposite to anObjecttype in Java which is a supertype of all types.

The Rules

Coercions vs Subtyping

Rust has a set of rules that allows one type to be coerced to another one. While coercions and subtyping look similar it is important to differentiate one from another. The key difference is that subtyping does not change the underlying value while coercion does. Specifically, the compiler inserts some extra code at the site of coercion to perform some low-level conversion, while subtyping is just a compiler check. Since this extra code is hidden from the developer, coercions and subtyping look visually similar, because both might look like this:

let b: B; ... let a: A = b;

Side-by-side coercion and subtyping:

// This is coercion:

let values: [u32, 5] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let slice: [u32] = values;

// This is subtyping:

let val1 = 42;

let val2 = 24;

'x: {

let ref1 = &'x val1;

'y: {

let mut ref2 = &'y val2;

ref2 = ref1;

}

}

This code works, because 'x is a subtype of 'y and so &'x is a subtype of &'y.

It is easy to differentiate the two by learning some of the most common coercions, the rest are much less frequent, see Rustonomicon:

- Pointer weakening:

&mut Tto&T -

Deref:

&xof type&Tto&*xof type&U, ifT: Deref<Target=U>.

This allows using smart pointers like they were regular references. -

[T; n]to[T]. -

Ttodyn Trait, ifT: Trait.

You might wonder why the fact that 'x is a subtype of 'y implies that &'x T is a subtype of &'y T? To answer this we need to discuss Variance.

Variance

It is easy to tell whether lifetime 'longer is a subtype of a lifetime 'shorter based on the previous section. You can even intuitively understand why &'longer T is a subtype of &'shorter T. But can you tell whether &'a mut &'longer T is a subtype of &'a mut &'shorter T? It is actually not, and to understand why we need the rules of Variance.

As we said before, lifetimes enable limited subtyping on types that are parameterized with lifetimes. Variance is a property of the type-constructors, where type-constructor is a type with parameters, e.g. Vec<T> or &mut T. Specifically, variance determines how subtyping of the parameters affects the subtyping of the resulting type. If type-constructor has multiple parameters, e.g. F<'a, T, U> or &'b mut V, then the variance is computed with respect to each parameter individually.

There are three types of variances:

F<T> is covariant of T if F<Subtype> is a subtype of F<Supertype>

F<T> is contravariant over T if F<Subtype> is a supertype of F<Supertype> F<T>is invariant over T ifF<Subtype> is a neither a subtype nor a supertype of F<Supertype>, making them incompatible.

When type-constructor has multiple parameters, we can talk about individual variances by sayint that, for example F<'a, T> is covariant over 'a and invariant over T. Also, there is actually a fourth type of variance, bivariance, but it is a specific compiler implementation detail which we do not need to touch here.

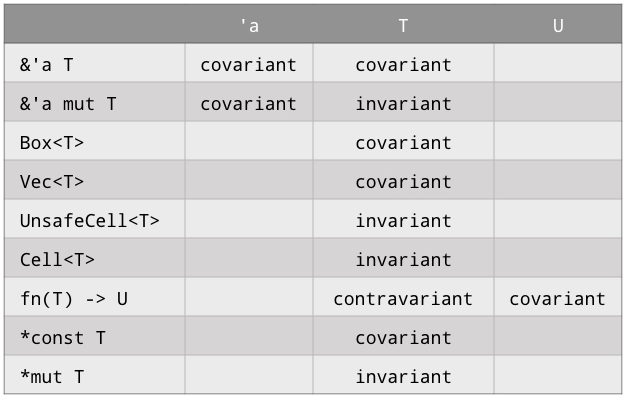

Here is the table of variances for most common type-constructors:

Covariance is basically a pass-through rule. Contravariance is rare and occurs only when one passes a pointer to a function that uses higher-rank trait bounds. Invariance is the most important one and we will see its motivation when we start combining variances.

Variance arithmetic

Now we know what are the subtypes and supertypes of &'a mut T and Vec<T>, but do we know what are the subtypes and supertypes of &'a mut Vec<T> and Vec<&'a mut T> ? To answer this we need to know how to combine variances of the type-constructors.

There are two mathematical operations for combining variances: Transform and the greatest lower bound, GLB. Transform is used for type composition, while GLB is used for all aggregates: struct, tuple, enum, and union. Let us denote in-, co-, and contravariance with 0, +, and -, respectively. Then Transform(x) and GLB(^) are described with the following two tables:

Example

Suppose we want to know whether Box<&'longer bool> is a subtype of Box<&'shorter bool>. In other words, we want to know the covariance of Box<&'a bool> with respect to 'a. &'a bool is covariant with respect to 'a and Box<T> is covariant with respect to T. Since it is a composition we need to apply Transform (x): covariant (+) x covariant (+) = covariant (+). Which means we can assign Box<&'longer bool> to Box<&'shorter bool>.

Similarly, Cell<&'longer bool> cannot be assigned to Cell<&'shorter bool> because covariant (+) x invariant (0) = invariant (0).

Example

The following example from Rustonomicon demonstrates why we need invariance on some type-constructors. It attempts to construct a code that uses a freed object.

fn evil_feeder<T>(input: &mut T, val: T) {

*input = val;

}

fn main() {

let mut mr_snuggles: &'static str = "meow! :3"; // mr. snuggles forever!!

{

let spike = String::from("bark! >:V");

let spike_str: &str = &spike; // Only lives for the block

evil_feeder(&mut mr_snuggles, spike_str); // EVIL!

}

println!("{}", mr_snuggles); // Use after free?

}

Rust compiler would not allow it. To understand why we first desugar some of the code:

fn evil_feeder<’a, T>(input: &’a mut T, val: T) {

*input = val;

}

fn main() {

let mut mr_snuggles: &'static str = "meow! :3";

{

let spike = String::from("bark! >:V");

‘x: {

let spike_str: &’x str = &’x spike;

‘y: {

evil_feeder(&’y mut mr_snuggles, spike_str);

}

}

}

println!("{}", mr_snuggles);

}

During compilation, the compiler will try to find parameter T that satisfies the constraints. Recall that compiler takes the minimal lifetime and so it will attempt using &'x str for T. Now, the first argument of evil_feeder is &'y mut &'x str and we are trying to pass &'y &'static str instead. Will it work?

In order for it to work &'y mut &'z str should be covariant over 'z, because 'static is a subtype of 'y. Recall that &'y mut T is invariant with respect to T and &'z T is covariant with respect to 'z. &'y mut &'z str is invariant with respect to 'z, because covariant(+) x invariant (0) = invariant (0). So it will not compile. The crisis has been averted!

Interestingly, this code would compile if written in C++.

Example with structs

With structs, we would need to use GLB instead of Transform, but it only matters for when contravariance is involved which only happens when we use function pointers. Here is an example that will not compile, because struct Owner is invariant with respect to lifetime-parameter 'c, which is also indicated by the compiler error message: type annotation requires that `spike` is borrowed for `’static`. Invariance essentially disables subtyping and so the lifetime of spike should match mr_snuggles exactly:

struct Owner<'a:'c, 'b:'c, 'c> {

pub dog: &'a &'c str,

pub cat: &'b mut &'c str,

}

fn main() {

let mut mr_snuggles: &'static str = "meow! :3";

let spike = String::from("bark! >:V");

let spike_str: &str = &spike;

let alice = Owner { dog: &spike_str, cat: &mut mr_snuggles };

}

Outro

It is hard to memorize all these rules and we do not want to search through them every time we encounter a difficult situation in Rust. The best way to develop intuition is to understand and remember unsafe situations that these rules prevent.

- The first example with shifting coordinates allows us to remember the borrowing rules that prevent simultaneous mutation and aliasing.

-

&'a Tand&'a mut Tare covariant over'abecause it is always ok to pass a longer living lifetime where the shorter one is expected, except when they are wrapped in mutable reference and alike. -

&'a mut T,UnsafeCell<T>,Cell<T>,*mut Tallow mutable access and so to prevent the aboveevil_feederexample and alike we want it to be invariant overTwhich implies an exact match of the lifetimes.

With each release, Rust moves in the direction of usability and friendliness, however, lifetimes is a core concept that still requires a deep dive. This post assembled information from various resources so that you make one deep dive instead of many 🙂

Credits

The following resources were used to compile this post:

- The entire Rustonomicon is a journey through ownership, borrowing rules, and lifetime.

- Variance in Rust by kennytm does some ol’ compiler source code reading to present us with rigorous rules of Variance and Variance Arithmetic.

- Subtyping and coercion in Rust by Nick Cameron discusses differences between coercion and subtyping.

Finally, thanks to Michael Kever, David Stolp a.k.a pieguy and everyone else in our Near Protocol team for the discussions of the lifetimes. For those interested in Near Protocol: we build a sharded general purpose blockchain with a huge emphasis on usability. If you like our write-ups, follow us on twitter to learn when we post new content:

If you want to be more involved, join our Discord channel where we discuss all technical and non-technical aspects of Near Protocol, such as consensus, economics, and governance:

Near Protocol is being actively developed, and the code is open source, follow our progress on GitHub:

https://upscri.be/633436/

Upd

- According to @centril,

fn announce(value: &impl Display)tofn announce<'a, T>(value: &'a T) where T: Displayis not an actually valid in-language desugaring, because turbofish will not allow applying a type like that. However, the point still stands; - In this post, we said that lifetimes are not types, but for simplicity we decided to call them types. Also, as pointed out by @centril lifetimes are what is called type-like.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog